Recently, I’ve tested a few people with low vision.

A couple of months ago, Mrs T came into our practice, accompanied by her husband. She has glaucoma and uses a white cane when getting about. Her loss of vision is so advanced that she is registered as partially sighted (and has been for some time).

After checking her details, I offered her my arm and we went through to the test room. When we got to the chair, I put my hand on it and she used my arm as a guide to find the seat and sit down.

“Where did they teach you that?” she asked. “My husband still struggles to remember.”

I laughed and said it was something we were taught at uni. It’s such a small thing but it does show that you understand how to support a visually impaired person (VIP). It gives them a little more confidence (as well as making you look good).

Anyway, Mrs T was a delight. Although her vision was limited to 6/60 (with a visual field so tiny that fields were almost impossible), she travelled, socialised and seemed to have adapted to her field loss very well. She said did struggle with reading, though.

Testing someone who is 6/60 corrected is difficult. You want to make sure their vision is as good as it can be but you don’t want to spend too much time asking them again and again what they can see – it reminds people of their loss and can be quite depressing. At 6/60, you should refract with +/-1.00DS to start. Use the strongest cross cyl that you have and a large, round target. You may have to print out a 6/60 size “O” and attach it to the wall for your VIPs.

After refining her distance vision, we moved on to her reading add. Now, for my VIPs, I don’t hand them the near chart open at N5 to N8 (we have a book style one). I start with the largest font size and then ask them if they can read smaller and smaller. If someone can see the first thing they look at, then that’s great – they feel positive. It’s depressing to say “no” continually when asked if you can see something so start with a letter size you think they’ll find easy and go from there.

In Mrs T’s case, we managed N24, which was actually a bit better than what she’d achieved previously. I made sure to tell her this.

I also asked what visual aids she had at the moment. Out came a folding, self-lit magnifier from her massive hand bag. She also had other magnifiers in the house. I asked how she was getting on with these and which glasses she used with each one. Mrs T was a pro with all the magnifiers: she knew the hand held ones needed the distance glasses and the stand ones her readers.

At the end of the test, again, I offered her my arm and we went through to have a look at glasses.

A few days later, Mr and Mrs T returned to collect her specs and I made sure they were fitted perfectly and that she was happy with the tints. I handed her the near chart to try with her new reading glasses and she could read N18. That was wonderful.

Tints and photo-chromatic lenses are very helpful for our low vision patients. Reds, browns, oranges and yellows seem to improve contrast and reduce glare in those with advanced glaucoma, AMD and other retinal issues. You might have to experiment with the colours to see what works with each patient (this is much easier if you work in a practice that tints onsite).

As I mentioned, Mrs T was a lovely, chirpy person – a complete contrast to the next patient I’m going to write about.

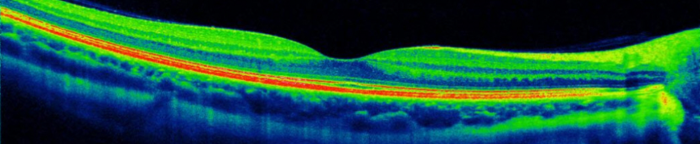

Mrs J attended for her routine eye test a few weeks ago. She came in looking pretty grumpy and was quite curt to L during the pre-screening. When we got into my room, she told me she had wet AMD in both eyes and that her right eye was “completely gone”. She was attending HES for monthly Lucentis injections in her left eye.

As I may have mentioned before, I’m very good with grumpy people. I am relentlessly cheerful at them until they give in and smile. L, our receptionist, is always surprised when someone goes into my test room looking like a bear with a sore head and comes out laughing and smiling.

Anyway, like many of my patients, Mrs J was grumpy because she was worried. She was amazingly healthy for a 75 year old Scot but was going blind in both eyes. She, like Mrs T, loved to travel and socialise, both of which she could do at the moment but she was concerned about her vision limiting her in the future.

After a thorough history and symptoms, I asked her to cover her left eye so I could check the vision in her right.

“It’s no good. I can’t see anything in that eye. It’s away.”

“Don’t worry, just look over at the chart, can you see letter at the top?”

“No, it’s pointless. I can’t see anything,” she went to uncover her left eye but I stopped her.

“Okay, so how many fingers am I holding up?” I asked, moving my hand into her peripheral vision.

“Three,” she said.

“Perfect.”

We moved onto the left eye and found that there had been a slight change in her prescription since her last test. She was 6/12 and N6 in that eye.

As I was doing the test, we were chatting about holidays and it turned out that she was going to Devon at the end of May. I’d been there in September last year and had loved it. We ended up talking about Ottery St Mary*, Dartmoor and fossil hunting.

When we left the test room, we were still chatting away. I took the fundus photos, did non-contact tonometry again and then helped her choose her specs.

When Mrs J left, her attitude had completely changed – she’d visibly relaxed. That’s the benefit to focusing on what a patient can do and see rather than try to slavishly follow your usual routine, it makes the test a more positive experience.

When I was at uni, one of our lecturers said that the difference between an average optometrist and a great one is not clinical ability: it’s communication. Every day, I’m reminded of this – good communication can be the difference between a happy, well informed patient and a patient going home and googling the phone number for the GOC.

It’s also the difference between an optom with cake and one without cake:

* Birthplace of Samuel Taylor Coleridge